So you have finally bitten the bullet and left the fold of higher education. Perhaps your departure was voluntary, perhaps it was not. The reality is, the journey of a recovering academic may be difficult for some time.

This article provides a twelve step guide to help the recovering academic make the transition to a new, post-academic life and realise there is life outside the academy.

- 1. Admit you have a problem

- 2. Write down the harmful effects of being an academic

- 3. Redefine what success means to you

- 4. Audit your skills and expertise – decide what legacy you want to leave

- 5. Replace old, bad habits, with healthy new ones

- 6. Set a start date for your academic recovery

- 7. Seek professional help

- 8. Reacquaint yourself with your loved ones

- 9. Prepare your academic recovery environment

- 10. Learn to say ‘no’

- 11. Sort out your finances

- 12. Celebrate your accomplishments

1. Admit you have a problem

As with all recovery programs the first step is admitting you have a problem.

Recognise what this actually means.

Like all academics, you probably went into your career to make a difference to society and humanity. No doubt you succeeded in some way. But in doing so, your identity has probably become synonymous with your H-Index, grant outputs, publications, your most recent student reviews, the number of committees you sit on, the number of cups of coffee you drink and your ability to stop at half a bottle of wine.

If this is you, then you have a problem.

Stand in front of a mirror, look directly into your eyes, and say out loud, “I’m an academic!”

It’s OK – recovery is within your reach. We are here to help.

2. Write down the harmful effects of being an academic

Do you check your Google Scholar profile when you wake up each day to see how many citations you have?

Can you cite your current H-Index without looking it up?

Or are you exhausted and overwhelmed from the number of committees you sit on and courses you teach?

If you answered yes to any of the above, it is time to find some new metrics for success.

Perpetual multitasking, the inability to say ‘no’, committee-itis, too much travel, office politics, constantly striving for something else, imposter syndrome, the endless treadmill of applications – rejections – applications – successes – completion – delivery – application – publication etc. It’s exhausting just writing it.

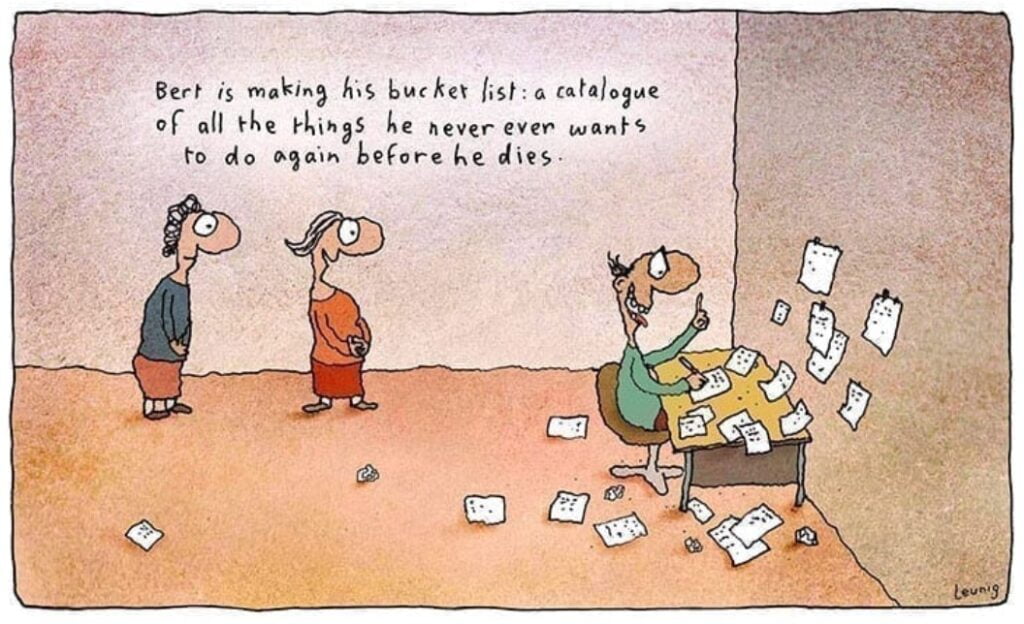

Write down all the things you never want to do again as a recovering academic and make sure you hold yourself to account.

Purging the baggage is the beginning of your new, post-academic identity.

3. Redefine what success means to you

Now that you’ve detailed all the negative effects of your addiction, think about how much your life will improve once you’ve kicked the academic habit. Create a picture of your life post-academic recovery life. How do you want it to look?

- No more deadlines.

- Read for enjoyment, not for employment.

- Browse glossy magazines instead of journal articles.

- Enjoy weekends, instead of collapsing from exhaustion.

- Eat lunch.

- Eat lunch at a table with other people, not at your computer.

- Never complete another ethics application, grant application, collect more data, write a report, prepare for lectures, or go to another academic board meeting.

I have moved through life saying “yes” to nearly every opportunity that came my way, believing subconsciously that busy-ness was synonymous with success. It was certainly the path to recognition and senior roles, but is that the same as success?

What I know now is that busy-ness is a path to destruction, inefficiency and the constant feeling of failure at nearly everything.

Develop some clarity about what is important and invest your resources in areas that really matter.

Success for me now is time with family, autonomy, being able to choose the work I want to do, and say “no” to the work I don’t want to do.

Be aware of living other peoples’ successes vicariously. Since announcing that I was a self-employed recovering academic, a number of well-meaning friends have sent me links to J.O.B.s that would put me straight back on the treadmill. People are fearful of your choices and want you to take their familiar, safe, busy journey.

If you need inspiration, there are lots of resources available, but a good place to start is Robert Waldinger’s TED talk “What Makes a Good Life” (spoiler alert – the quality of our relationships is key). Take a look at Simon Sinek’s TED Talk on How Great Leaders Inspire Action, which refocuses on “why” not “what” (an important mind shift for academics).

I’m also a huge fan of Scott Pape (the Barefoot Investor). Scott is an unconventional financial advisor who lost everything in the Victorian bushfires. Losing everything taught him what is valuable (good pillows and underpants in his case). But while he is clearly extremely successful, he is a strong promoter of making memories that people cherish. If you feel up for a little cry, then read this story on Scott Pape, The Barefoot Investor, to see what it’s like to lose your home.

4. Audit your skills and expertise – decide what legacy you want to leave

As academics, we tend to have a fairly narrow view of our own set of skills and expertise. For instance, if you have been a researcher, then it is easy to focus on your research subject area as your primary area of expertise. Similarly, if you have been a teaching scholar, you may define yourself as a teacher of [insert subject area].

However, without realising it you have amassed an enormous portfolio of skills that have the potential to lead into new and different roles. You need to identify those skills and will probably need to think about them differently.

If you read our blogging your research article, you will see that from one report, you can identify several niche areas of expertise from a single research project (such as a PhD). This will include your content and methodological expertise, research management and governance processes, public and patient involvement / community engagement, grant writing, report writing, networking, analysis and synthesis skills.

Your networks are also an incredibly valuable source of inspiration, support, and potential new areas of work.

A transition is also a good time to reflect on your portfolio of knowledge through different eyes. My best work has come at times of major personal transitions by allowing me to look at my existing knowledge through a different lens.

For instance, my research field is allied health workforce research and I have spent the past 20 years looking at this from a range of different angles, in different countries and across more than 30 different professions. With a colleague, who is an expert in sociology, we were able to take a very macro view of our work to produce a high level synthesis on the sociology of the allied health professions which we have published as a book. It was a very satisfying opus magnum of our combined academic careers and will lead to other opportunities and outputs which can generate income. A sort of therapy for the recovering academic!

Don’t just consider your academic skills. Your personal interests and hobbies may be a valuable source of new inspiration, and may even be the seed for a side hustle which could generate income.

Alternatively, you may have the ability to contribute to a cause that you are passionate about through political involvement or taking a role in a not-for-profit organisation or other charity.

5. Replace old, bad habits, with healthy new ones

Instead of reaching for your phone / computer first thing in the morning to check your emails, make a conscious decision to start new activities that will bring pleasure and meaning to your life.

The time and energy you may have spent writing journal articles could be redirected to your new novel, playing an instrument, gardening, or doing sport.

6. Set a start date for your academic recovery

Give yourself time to finish your important commitments. Tell others that you are not taking on any more academic roles.

You also need this time to help you find alternative activities to help your academic recovery.

Don’t expect that you will be able to walk away entirely guilt and commitment free. Most recovering academics I know are still supervising PhD students and chairing committees several years after quitting academia.

Pick a date that’s meaningful to you. A significant birthday, the date of your last PhD student graduation etc. Try to make sure it is within your reasonable life expectancy!

Mark the date on your calendar and announce it to those likely to put demands on you. Build up to it so you won’t be likely to back down when the day arrives. Make a firm commitment to yourself that you’re going to quit by that date.

Ensure you have all of your distractions adequately in place to keep you busy.

Plan a celebration to mark the transition to your new life.

7. Seek professional help

If you’re reading this, you have probably already sought professional guidance.

Career coaches or executive coaches can be invaluable at helping the recovering academic understand the options available to you with the skills you have. They can also help guide you through the inevitable challenges that come with your employment transition. Depending on your circumstances, you may be able to access professional support through your employer.

Counseling or mental health support may also be helpful. Despite all of the positive things ahead of you, you may go through phases of loss, grief, anger and depression as a result of changes to your identity. Having the support of a professional and the structure of a framework to guide you through these changes can be invaluable. Most universities will have access to counseling or support services for employees, but you may need to access it before you depart.

8. Reacquaint yourself with your loved ones

One recovering academic friend of mine told me that until he left the university, he didn’t know the name of his son’s friends or primary school teacher.

The spouse / partner who has adapted to the peaceful (or lonely) life of being an academic spouse will also need some preparation for the transition.

Most working parents will be juggling the guilt and challenges of having missed several important milestones in their kids’ development. It can be difficult to try to reacquaint yourself with your children when all they want to do is be with their friends, or worse, on their phone (which I think is the same thing these days).

You can do it – it just takes time.

Find your community. When Covid first hit, we were all told that we would grieve the loss of our community – our work colleagues. What I discovered, and I suspect many others did too – my community is around me. My neighbours, my local friends, the people I play pub trivia with, the people who queue up at the same time each day at the local cafe, the cafe owners. It might be your sporting club or church that meets that need.

These are the people who are there when you need them, not your work colleagues (in most cases). Invest your energy in the people who are going to support you and help you grow in your new stage of life. Learn how to be a friend and part of a community.

9. Prepare your academic recovery environment

Remove any triggers of your academic addiction from your home, car, and workplace. Get rid of all the objects that go along with your academic habit, as well as other items that are constant reminders.

- Remove all work related apps, especially email, Outlook and Google Scholar, from your phone.

- Keep your computer out of the bedroom.

- Put an out of office reply on your email stating that you only check emails periodically and it may take a while to receive a reply.

- Put textbooks, journals and other (now) useless papers in a box in the garage until you are ready to give them away or recycle them.

- Block toxic work numbers. Better still, get a new phone number and only reconnect with friends and colleagues you actually want to communicate with.

10. Learn to say ‘no’

Part of the academic addiction is that you still want to feel needed. You want to feel valued. You want to know that your 10, 20, 30 or more years of academic commitment haven’t gone to waste – that someone still wants you.

That’s fine, but think about how you want to be needed and valued and by whom.

An important part of the academic culture is that academics are ultimately altruistic.

ALTRUISM + YOUR NEED TO FEEL VALUED = POVERTY

You have left higher education. You may need to earn a living.

Those most hungry to value your expertise are the least likely to pay you. For example, journal editors seeking peer reviewers for journal articles. Like many others I still get daily requests to peer review journal articles. Sorry Elsevier and Springer, you won’t like what’s coming – but say “NO”.

Other people keen to value your expertise are PhD supervisors at other universities seeking PhD examiners. Several days of work for only four hundred bucks? It’s your choice.

Committees are also keen to seek out freshly recovering academics. “Perhaps you could just sit on this (voluntary)… committee?” Flattering perhaps, but does it fulfill your new definition of success?

A recovering academic colleague of mine who retired two years ago is still doing intensive pro bono committee work because he doesn’t want to feel indebted to the organisation he is working with. I suggested to him that it should be the other way around.

Consider your years of education and experience and put a reasonable financial value on your daily rate. Ask around and find out what consultants in your field are charging. Don’t be afraid to ask for what you are worth and consider the opportunity costs of doing versus not doing the work. Would you rather be gardening? Surfing? Traveling?

I know because I’ve done and continue to do all of these things, but I’m slowly extricating myself from these obligations.

11. Sort out your finances

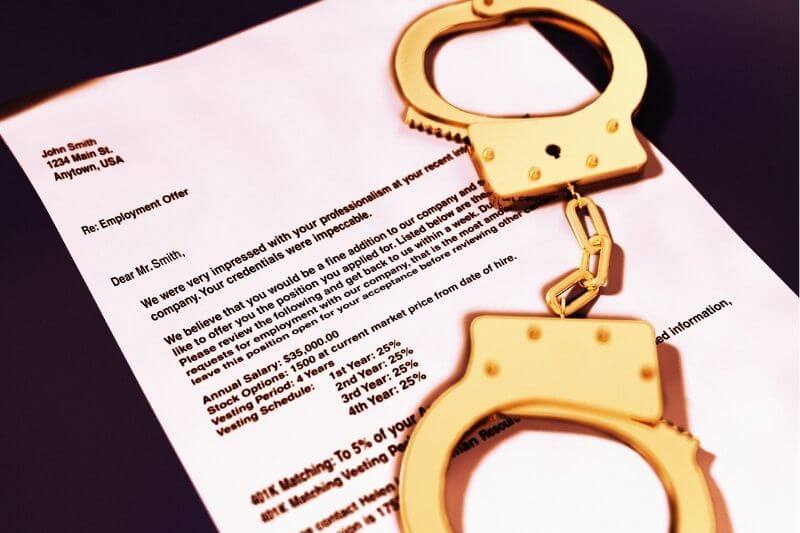

In most high income countries, academic salary packages include a reasonably generous pension or superannuation allowance. In fact, the reason a number of people remain in higher education longer than they should is because of the “golden handcuffs”, or the benefits and the high opportunity cost of leaving their university job.

I’ve put this towards the end because chances are you have either sorted this out by the time you have left the academy, or you had no choice but to leave.

I am not a financial advisor so am not authorised or certified to give financial advice. Your pension or superannuation fund are likely to have an advisor or financial planner you can access for free or at a low cost.

Alternatively there are several financial advice services available. Ask for recommendations and do your homework before you commit to a single service.

Prepare a budget. Know what your regular expenses are and those that are likely to continue once you leave work. It helps to know what your minimum survival costs are and to have a plan for how you might cover those if you are making a large transition with some risk.

Look at the expenses that will reduce, or, in some cases increase. Vehicle and travel costs, health insurance, income protection insurance, your telephone, office and computer costs are all things you may need to consider.

If you are making a major transition, for instance into self employment, ensure that you have sufficient funds to cover long periods of uncertain income. Consultant friends of mine regularly have between 6 – 12 months of income available in case of lean times.

If you have been forced into the transition and have not been able to prepare for your change of circumstances, reach out to your networks quickly to find alternative work, and find out what your financial options are.

We have resources on how to prepare your CV and to stand out to recruiters in case you need to look for other roles within the academy.

12. Celebrate your accomplishments

A few months ago I re-discovered the 10 year plan that my best friend and I wrote together when we were 18 years old. We had both well and truly exceeded those goals, but remained fairly true to the intent of them. Despite a few bumps, we are also still friends.

The timing of that discovery was serendipitous because it coincided with my “academic recovery”. There were a lot of things that happened that weren’t in the 10 year plan – many challenging things – but it was satisfying to remember where we had both come from and what we had both achieved.

We also set up our next 10 year plan (which included far more health, relationship and survival related goals than our more materialistic / lifestyle oriented plans at 18).

Don’t forget to take stock of what you have achieved and celebrate where you are now. There are still many great adventures ahead!